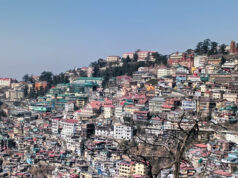

Shimla is once again at the center of a raging controversy over illegal construction, with the Shimla Municipal Corporation (SMC) seeking a one-time settlement for over 8,000 unauthorized buildings in the city. With nearly 25,000 such structures across Himachal Pradesh, the move raises serious concerns about urban planning, environmental sustainability, and legal accountability. However, history suggests that previous relaxations have only emboldened violators, leading to unchecked construction and worsening the city’s fragile ecosystem.

Decades of Violations and Failed Retention Policies

Illegal construction in Shimla is not a recent phenomenon. The city has witnessed rampant violations of building norms for decades, especially in the merged areas that were previously outside municipal limits. In a bid to regularize these violations, successive state governments introduced multiple retention policies, effectively rewarding illegal builders instead of penalizing them.

The state government had introduced various retention policies in the past providing relief to unauthorized structures. The policies were introduced under different governments, often just before elections, to appease voters and builders. However, rather than curbing illegal construction, these relaxations sent a clear message: violations would eventually be legalized.

The most controversial of these policies came in 2016, when the then-government attempted to regularize thousands of unauthorized buildings, including multi-storey structures in ecologically sensitive zones. The move was challenged in court, leading to a High Court ruling in 2017 that struck down the policy, citing its role in encouraging lawlessness in urban planning. The court observed that such amnesties had turned Shimla into an unregulated mess, with narrow roads, water shortages, and landslide-prone zones becoming a norm.

Despite this, in 2018, another retention policy was introduced, further emboldening violators. Builders, confident that future governments would grant them relief, continued to flout the Town and Country Planning (TCP) Act, 1977. This unchecked expansion, combined with deforestation and haphazard construction, has left Shimla struggling with severe infrastructural and environmental challenges.

Legal Hurdles and Environmental Fallout

The biggest roadblock to the Shimla MC’s latest push for legalization is the series of Supreme Court, National Green Tribunal (NGT), and High Court rulings that have categorically barred further retention policies. Courts have repeatedly slammed the state government, the TCP department, and municipal bodies for their failure to control unauthorized construction.

Illegal structures have contributed to severe environmental degradation in Shimla. Green felling for construction, encroachments on forest land, and the blocking of natural drainage systems have made the city more vulnerable to landslides and water scarcity. Shimla’s narrow roads, originally designed for a small population, now struggle under the weight of uncontrolled urbanization, leading to worsening traffic congestion and civic issues.

Shimla MC’s Push for Legalization: A Dangerous Precedent?

Despite past failures, the SMC is now advocating a one-time settlement, citing the Supreme Court’s approval of the Shimla Development Plan as an opportunity for relief. Councillors argue that these buildings, many of which lack access to essential services like water and electricity, need to be legalized to ensure proper urban planning. However, critics warn that such a move will once again incentivize further illegal construction, as past amnesties have done.

Urban planners and environmentalists have called for stricter enforcement of existing regulations rather than yet another blanket approval of violations. They argue that if the government bows to political pressure and legalizes these structures, it will set a dangerous precedent, undermining urban planning laws and encouraging future violations.

A Critical Test for the Government

The state government now faces a crucial decision: whether to uphold the rule of law and prevent further damage to Shimla’s fragile ecosystem or to cave into political and economic pressures by legitimizing decades of unauthorized construction. If another amnesty is granted, it could erode public trust in urban governance and send a clear signal that violations, no matter how blatant, will eventually be overlooked.

With Shimla’s ecological and infrastructural stability at stake, the government must weigh the long-term consequences of its decision. Will it prioritize sustainability and the rule of law, or will it repeat past mistakes, allowing unregulated expansion to push the city further toward an urban disaster?